Viewed 6872 times | words: 5621

Published on 2022-10-31 07:20:00 | words: 5621

As I wrote in the first article of this two-parts (and a book) series, this article was already seen, in a different format and content.

Probably you heard countless times the phrase "data is the new oil".

Paraphrasing what a famous economist said few generations ago, when even a tax driver was suggesting him which shares to buy, he knew it was time to bail out of the market.

No, I am not bailing out of the data-centric concept, I think that we need a refocusing of the concept.

I have been reading and re-reading few times Womack's book about that research on the automotive industry and its evolutions and impacts.

But the difference with oil is that data is not constrained to a limited number of processes or a physical supply chain and infrastructure development, to be embedded into decision-making and have impacts.

Also, if our technology nowadays delivers countless ways in which data is produced, collated and collected, distributed, embedded within other data to be turned into information, the causal chain that we were used to with oil, refinery, physical logistics, and the associated conceptual law-making are obsolete.

If, as an individual, I wanted to extract and process oil, I would need massive capital and, probably, connections and a network to be able to carry out my plan.

With data, which are turning increasingly into open data, creating new processes and new ways to carry out the above mentioned processes on data, up to packaging and selling data at the end of few "transformation" pipelines that convert raw data into indicator, projections, etc, in our times does not require an upfront investment.

So, the economic policy of our countries, whose conceptual boundaries are often not even linked to the post-WWII reality, but to a mindset defined in the 1920s to 1930s, is often influencing regulatory approaches that ignore a data-centric reality, including within financial markets.

As I wrote in the past, in the early 1990s, when Italy's currency was under attack, I saw first hand the side-effects of a data-centric, borderless financial world.

I went to visit my girlfriend in Germany (we met in Amsterdam), and started with an exchange rate of 720 ITL to 1 DEM, but in few months ended up paying 1200 ITL for 1 DEM.

Human capital and economic development in a sustainable way cannot ignore the data dimension, as it influences not just perception, but individual choices that then in turn develop further layers of perception: filter out data that are relevant, and your decision-making might end up taking more than a few wrong turns, or, at least, put you out of tune with the foreseeable common wisdom.

If the previous article was about the systemic context, today is about the process.

But before, shared yesterday morning a post on the personal context of my observations, with the title "Crossing the bridge".

The process, of what, you would say? Of caring about human capital and policy in a structured way- what is usually called an "industrial policy", specifically in Italy ("politica industriale"), while elsewhere might have a broader definition.

Anyway, just a preamble to contextualize, and a warning.

The warning is simple: as I shared some ideas in the past that attracted at least few thousands on each article, this article is also a kind of cross-reference to previous articles, with few quotes here and there- no point in reinventing the wheel, just updating it a little bit- also in preparation of a forthcoming (data-centric) book.

As hinted above, words have a cultural influence- e.g. in Italian "processo" means both "process" and "(jury) trial".

The commencement/introductory conference speech I heard at London School of Economics Summer School (I do not remember if in my attendance in summer 1994 or summer 1995) had a curious concept.

It was about how in different languages a square (I mean the physical space generally between buildings or crossroads, i.e. ) was described.

The funny part was when he compared the Italian or French or Spanish words for "square" (piazza, place, plaza): his theory was that the sound, in and by itself, showed how we Italians, French, Spanish saw the physical place as something open, not closed, while the English "square" spelled of a different story.

The "process" within the title is of course has nothing to do with the Italian meaning of "jury trial".

Instead, I am referring to what ISO9000 defines as "set of interrelated or interacting activities which transforms inputs into outputs" (or, also, ITIL v4 "A set of interrelated or interacting activities that transform inputs into outputs. A process takes one or more defined inputs and turns them into defined outputs. Processes define the sequence of actions and their dependencies").

Actually, a process that in the future should probably look more as a service, which ITIL v4 defines as "A means of enabling value co-creation by facilitating outcomes that customers want to achieve, without the customer having to manage specific costs and risks."

As hinted at within the closing section of the previous article, in this article will have to consider few elements:

_how AI and Edge computing might influence industrial and corporate policy interact(ions) with human capital development

_the concept of sustainability at an individual, social, and organizational level (not just for communication)

_which new tools and organizational structures could be useful, looking forward

.

But, of course, those are not the sections of this article, just some key data-centric concepts (and their potential systemic impacts).

These will the be sections:

_industrial policy and NextGenerationEU

_the supranational butterfly effect

_from static to dynamic industrial policy

Industrial policy and NextGenerationEU

As I wrote in the previous article:

"What is an industrial policy?

In Italy, apparently a pipedream."

As I shared before, one of the most frequently read articles on this website contained just few concepts about definiting an industrial policy that would last longer than an electoral cycle (Per una politica industriale che veda oltre le prossime elezioni #industry40 #GDPR #cybersecurity / For an industrial policy that survives election cycles #industry40 #GDPR #cybersecurity).

The real issue is cultural: an industrial policy implies a concept of "common interest", while in Italy, as I keep repeating, we are still too tribal.

Hence, any attempt usually results in a convergence of interests that produces supposedly long-term policies that actually deliver short-term adjustments, before being tinkered with or even scrapped and replaced.

Or even, as it happened in the past, long-term in expectation and "marketing", but then renewed and tinkered with at least once a year.

A further element: way too often in Italy you will read and hear as if Italy were able to design and deliver an industrial policy all by itself, and then have the world tune with it.

In spring 2019, right before the European and Regional elections, posted on my blog an article with a mouthful of a title: "2019-04 #Italy, A country between Milgram, Zimbardo, Hawthorne, and... a Gaussian distribution ( #RegionaliPiemonte and #EuropeanParliament2019 during #Brexit series )".

The themes discussed in that 2019 article are the same we are discussing now, in 2022.

In Italy, whenever there is an external crisis, we piggyback our structural issues to it.

Why? To procrastinate structural changes, trying to blend our pre-existing conditions with the new crisis, to avoid having to deal with our mutual tribal obligations that generate long-term structural impacts (call it "retaliatory economic policy").

It happened with the 2008 financial crisis: I had reports from Italy about crisis from at least the early 2000s, up to the point that back then proposed to a partner in German Switzerland to "near source" software development in Italy, as would have been cheaper than shuttling people from Asia or Canada.

But when I routinely attended workshops and conferences in Italy from 2012, I kept hearing (and reading) about the "crisis of 2008" as it had been wrecking a perfect economy.

Most of the first conferences I attended in Italy since 2012 routinely reported that the equipment used by our companies often was quite old- hence, incentives to replace equipment with more modern equipment were routinely demanded.

Eventually we got laws to promote replacing equipment with equipment ready to support the more data-centric "Industry 4.0", i.e. equipment able to continuously provide data to corporate (and, why not, eventually also government) information systems, to e.g. help tune use, predict maintenance needs, support better use of utilities, etc.

I already wrote back then and routinely in my articles about some "quirks" in those laws, e.g. it took a while before moved from being a year-by-year renewal to something more or less aligned with the (accounting) life of the equipment, and it was a while before covered also the costs associated with training and connecting that equipment with corporate information systems.

But, again, reading those laws, also when nominally had been "created" by somebody who continuously repeated of his past as manager in multinational companies (it is always a collective and bureaucratic staff affair, also if presented as a "lone ranger effort"), I always wondered if those lawmakers had any clue about what could be the impacts.

Yes, the First Republic (roughly late 1940s to early 1990s) ended in scandals, but at least senior politicians back then had a more "systemic" understanding.

As I shared in 2019:

A quote from a 2016 article celebrating the 25th Anniversary of the Maastricht Treaty (https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/commenti-e-idee/2016-01-22/l-europa-maastricht-nasceva-25-anni-fa-momento-decisivo-la-nostra-storia-recente-145406.shtml?uuid=ACHrxQFC): "Il 7 febbraio del 1992 ad apporre la firma sul trattato di Maastricht c'erano per l'Italia Andreotti, all'epoca a capo del suo settimo e ultimo governo, insieme al ministro del Tesoro, Guido Carli. Si dice che sulla via del ritorno da Maastricht a Roma Carli abbia commentato: "Nessuno in Italia è consapevole degli effetti che questo trattato avrà sul nostro Paese".

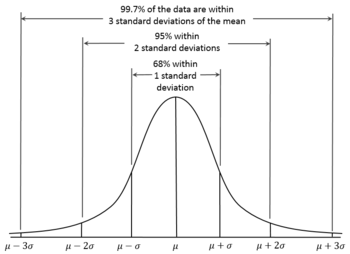

It seems that we still haven't yet fully understood the cultural changes required to move toward the center of the Gaussian distribution (picture from the Wikipedia page https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Normal_distribution).

. In 2022, we are apparently still unable to understand if what we negotiate is aligned with our current capabilities or, at least, our capabilities to reform to get into that "center".

Meaning: Italy, even before NextGenerationEU, routinely proved to be unable to spend all the resources that was assigned.

That, thanks to the NextGenerationEU facilities to support digital and green transition, we are injecting significant amounts within the economy and expanding investments while trying to accelerate our traditional slow spending abilities, does not necessarily means that we will change at the same speed the capabilities.

As shown by the recent release of information about the actual spending schedule, that shuffled toward the end some spending.

Let's just say that we have been waiting since 1992 to really converge to the middle of that curve, and hopefully this massive injection of funds and "facepalm" risk will help at last implement much needed structural reforms, i.e. will help to overcome tribal objections.

The latter, joining forces across the tribes for a shared purpose- a kind of "national interest"-oriented systemic view.

As I wrote in 2021 when I did share information from the civil society presentations to "feed" ideas to politicians about potential projects for the PNRR, we had still too much of a tribal element, and few presentations looked at the whole picture you can see here and on GitHub the information and documentation.

The alternative? The Italian version of something more common since the Treaty of Rome was signed.

Again from that 2019 article:

"The subject, in this case, is supposedly the European Parliament elections at a time when, thanks to Brexit, the European Union is both restructuring and soul-searching (and, ça va sans dire, trying to rebalance the distribution of powers: Monnet method, crises are what enabled most reforms, since the Treaty of Rome): "The problems that our countries need to sort out are not the same as in 1950. But the method remains the same: a transfer of power to common institutions, majority rule and a common approach to finding a solution to problems are the only answer in our current state of crisis" (Monnet 1974, quoted by Mario Draghi at the Award of the Gold Medal of the Fondation Jean Monnet pour l'Europe, Lausanne, 4 May 2017

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2017/html/ecb.sp170504.en.html )."

If you read previous articles on this website, you know what I think of tools and timing, e.g. on the Monnet method: A #Monnet moment? Different times require different tools #NextGenerationEU #crises #war #energy #democracy.

Anyway, the title of this section is again a reference to a concept that in my discussions seems elusive: it is not feasible to have a national industrial policy that ignores e.g. how many Italian companies, due to their small size, are "embedded" within the supply chain of larger companies based in other leading European Union Member States.

Long ago, was contacted to ask some questions about the datasets on the PNRR and NextGenerationEU that I shared since 2020 online (mainly on my Kaggle profile).

As in other cases, I replied that actually the answer I was giving where already online, within the documentation associated with each dataset.

But when I was also asked about the "cost benefit analysis of each one of the PNRR projects" (i.e. hundreds) I was puzzled.

A cost benefit analysis usually requires a team effort, if you want to do something more coherent with reality than mere "bean counting".

Hence, my standard reply to those and similar questions (I had many, in Italy) since 2008 is always the same: if I were to prepare something, it would be released online, as all the other material, where anybody from anywhere could have access to it- unless, of course, it were a project for a customer.

But, frankly, I would find quixotical an individual (or even a company) doing a cost benefit analysis on each one of the projects.

As each analysis implies time, resources, costs- and, except the European Union to check if the projects make sense, and, before that, the Italian State after receiving proposals, before assembling the documentation for Brussels (again, to avoid a "facepalm"), even a large company would probably focus just on specific areas where could be involved.

The point is that, if you want to develop an industrial policy for Italy in 2022, probably the best option is something more than what I saw during the preparation of the PNRR.

It is not a matter of collecting what each tribes wants- it is a matter of involving the tribes (yes, including the various business tribes) in defining priorities and "subsidiarity": an industrial policy that is based just on helicopter money is a waste of resources.

Priorities should be identified and defined, not necessarily at the national or Brussels level (we have "industrial districts" represented by supply chains that span multiple countries, not even physically directly connected).

Treaties such as the one of the Quirinale and the previous one at the Elysée in 1963 (de facto updated few years ago at Aix-la-Chapelle) probably can give an idea of the mechanics of transnational industrial policy development, associated to structural and continuous exchanges, instead of the usual "horse trading by committee".

The supranational butterfly effect

Over the last few weeks, there have been articles about the side-effects (somebody would call them "collateral damage") of the apparent disconnect between the main central banks, including between USA's Fed and EU's ECB.

But to coordinate the efforts of entities that answer to a different set of "owners" and a different mandate requires convergence of interests (and desired impacts).

From the Fed website::

What are the goals of monetary policy?

The Federal Reserve Act mandates that the Federal Reserve conduct monetary policy "so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates." Even though the act lists three distinct goals of monetary policy, the Fed's mandate for monetary policy is commonly known as the dual mandate. The reason is that an economy in which people who want to work either have a job or are likely to find one fairly quickly and in which the price level (meaning a broad measure of the price of goods and services purchased by consumers) is stable creates the conditions needed for interest rates to settle at moderate levels

From the ECB website:

The ECB provides one of those crucial internal anchors by pursuing its mandate of maintaining price stability in the euro area as laid down in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

In line with that mandate, our primary concern is, as always, our primary objective: price stability.

Therefore, that there might be different choices instead of "synchronized swimming", it is relatively understandable, as e.g. the effect on sustainable level of employment was recently discussed in USA as part of the reason of the rate increases.

But butterfly effects can also be at a much more indirect and smaller scale.

On the business side, the level of exposure to external tides varies on a country-by-country basis, and on an industry-by-industry basis, as well as the positioning within the supply chain.

So, what is a butterfly effect applied within the European Union industrial sector?

If German companies relocate away from Germany to, say, Spain or Portugal to benefit due to the energy costs after removing the supply from Russia, Italian companies in their supply chain will have at least few thousand kilometers more to deal with, and probably will have also to consider other issues.

At the same time, by relocating, those German companies would generate a significant impact on their own local communities, e.g. requiring a redefinition of the provision of services locally, or even public expenditure on services to citizens as well as welfare and health services or schooling.

In the XXI century, we have also been trying to reduce the travel of our produce and other consumables.

This article uses Italy as its focus: as I saw in Turin and overall read about Italy since the beginning of the COVID crisis, having smaller companies implies also that, if they are e.g. connected to the local supply chain catering for shops and restaurants feeding and clothing employees of public offices in major towns, once you turn most of them into remote workers, while at the same time increasing the energy costs (also because are spread across less customers), first shops, then small companies providing for those shops will have to reconsider their own business plans.

So, even if you had done a cost-benefit analysis in, say, summer 2020 for projects to be deployed until 2026, I wonder how much what was sustainable then would still be sustainable.

Yes, I know the objection: "but those were investment projects, so focused on the future".

As I wrote repeatedly, too much of the NextGenerationEU is on recovery, too little on either resilience or future generations.

Politically understandble: the dead and those not yet born do not vote.

But not really a sign of leadership.

And, of course, there is no need to read the hundreds of pages of those documents, to consider their impacts: in our times, you can have access to those with the right mix of knowledge, experience, skills willing to share their feed-back: just search online.

Therefore, the butterfly effect of incentives or disincentives can spread much faster than in the past, and generate what I could call "social resonance".

As I wrote often, it is not a matter of "fake news"- it is a matter of different viewpoints on the same information (and, as I keep writing, if you just focus on "real fake news", we had those already two thousands years ago, in Ancient Rome during political campaigns).

Considering the speed of dissemination of information, within the European Union we should actually expand our "four freedoms", at least to synchronize the speed of access to their use for all potential users (i.e. both individual and corporate citizens, not just the latter).

Of the four EU freedoms:

Free movement of goods

Free movement of capital

Freedom to establish and provide services

Free movement of persons

by personal experience in few countries, I must say that probably for individuals those covering goods and financial flows are more or less implemented (well, not really in Italy).

On the other two, free movement of persons works if it is temporary, but the freedom to establish and provide services still requires a lot of work.

At least as an individual, even after the Bolkestein directive was approved.

The level of mobility of European workers is nowhere close what my USA friends discussed with me while visiting them few times (and travelling once across the USA from Michigan to Arizona, but running across the North before crossing diagonally to get South).

It is not just a matter of languages- we are still 27 countries with 27 bureaucracies that have different ways of considering reality.

This would not be an issue if our companies and "flows" were mainly a bilateral affair, but first the COVID crisis, then the energy provisioning and cost crises associated with the invasion of Ukraine will continue to generate "butterfly effects" whose absorption could benefit from an easier way to relocate.

I remember decades ago about an experiment I think between Turin and a town in Finland on data exchange we were told about at a conference.

If a company, to cope with energy costs or a restructuring of supply chains, can move in months, the same should be possible also to citizens.

Anyway, as we have already those four freedoms, at least formally, this implies that, in our "dynamic" (not to say "chaotic") times we risk having butterfly effects that can make any industrial policy (that feeds the overall economic policy) less than feasible quite fast, if done just at the national level.

But it is not a matter to solve by creating the European Union equivalent of USSR's Gosplan, trying to plan left shoes and right shoes, as well as splitting production across all the COMECON to avoid that any satellite state could go "solo flying".

Instead, we should extract benefits from our data-centric economies whose national bureaucracies are massive data collectors.

From static to dynamic industrial policy

If you want to produce a static document and call it an industrial policy, get a bunch of people representing different knowledge domains somewhere, shut them in a resort, while providing catering, and in few days will give you an outline document useful to build a roadmap that can then be discussed or even turned into an operational guideline.

But we live in a data-centric society, and therefore, beside considering "who" should involved, "how" could be smarter than in past attempts.

In 2021 published a short article with the title For a forward-looking NextGenerationEU based on UN SDGs in Italy

As it was within the datademocracy section, shared data from 2020 "checkpoints on the state of the European Union", represented by UN SDGs:

" This short article is within the "data democracy" series, and for reasons that will be explained in few paragraphs.

It is about three themes, each closely interconnected, and therefore is not divided into sections: _ where is Italy now

_ NextGenerationEU / Recovery Plan from the UN SDGs viewpoint

_ the positioning of Italy vs. other EU Member Countries. " .

We are in 2022, so it is time to do a further check.

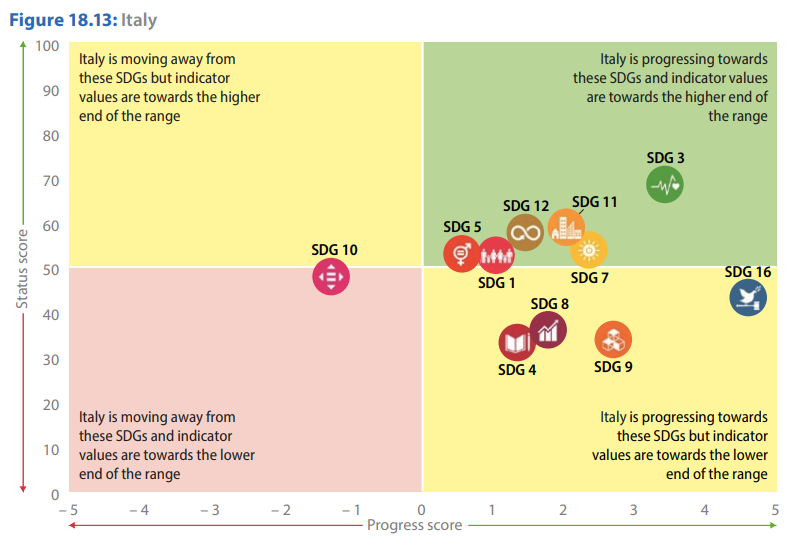

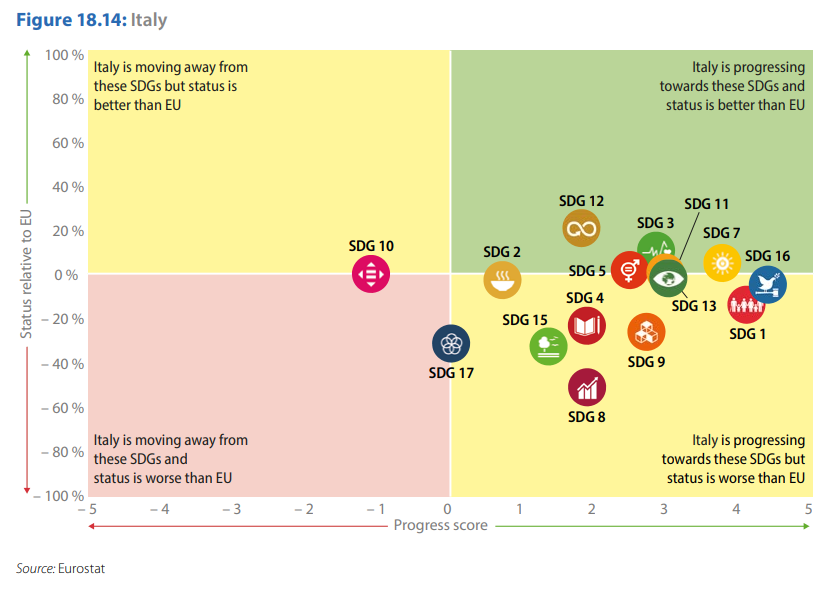

Lets' first see three "maps" concerning the EU, Italy, and SDGs in 2020:

And this is the status in 2022:

along with the prioritization:

What about Italy?

In 2020:

In 2022:

If you are interested in seeing more details, these are the documents (covering also the other EU Member States) in 2020:

_ Sustainable development in the European Union - Overview of progress towards the SDGs in an EU context - 2020 edition

_ Sustainable development in the European Union - Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context - 2020 edition

_ SDGs and me - 2020 edition (an interactive tool).

and in 2022:

_ ">Sustainable development in the European Union - Overview of progress towards the SDGs in an EU context - 2022 edition

_ Sustainable development in the European Union - Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context - 2022 edition

_ SDGs and me - 2022 edition (an interactive tool)

As I wrote above, in Italy we have always the risk of creating a "shopping list", not something aiming at a systemic change that would benefit the whole, as discussed in 2020 in another article that had more or less the same number of readers (few thousands, title: "Seizing the industrial policy opportunity: competence centers and recovery plan in Italy - thinking systemically"):

" In Italy, we still lack the implementation of two concepts: "civil service" and "common good"- it is yet another couple of elements worth investing on, e.g. by expanding the "in-house" capabilities of the former, and creating incentives (yes, why not, also through more "gamification") for the latter.

Just to avoid misunderstanding: "positive" gamification, not "negative"- on the latter, Italy has nothing to learn from China, but dis-incentives, in the end, stifle innovation and expand a local habit derived, in Italy, from centuries of rule by invaders.

Or: "second guessing" replacing "action", so that also any minimal action spreads resources across many options, just in case the power balance changes, and your favorite "action pattern" is not the one preferred by the new rulers...

Artificial intelligence now is not anymore as it was in the 1980s, when I was toying with PROLOG (well, a little bit more than that, as I recycled concept for a couple of decades in other business activities) and reading material on research on its potential applications in business as well as the military.

It isn't anymore about structuring human experts decision-making patterns into "expert systems".

It is more about contextual intelligence and integration in human activities- continuous adaptation.

Therefore, as it was for quality in the 1990s, cannot be added as a separate element, or as an add-on, an afterthought.

As I was reminding a friend a couple of days ago, after the reshuffling within the European Commission due to a commissioner creativity in compliance with COVID-19 rules, we have both in Brussels and Frankfurt, on economic dossiers, a "systemic" view.

Or: in Brussels, both Dombrovskis and Gentiloni are former Prime Ministers; in Frankfurt, Lagarde had "systemic" experiences via both her past political and IMF roles.

The current COVID-19 crisis has already shown systemic impacts also in countries where the real digital transformation had already started long ago (i.e. not just adding technology, but redesigning businesses- including what "work" means). "

Our European Union democracies are massive collectors of data- so, considering the complexity of exchanges (within each nation, within regions that cross boundaries, and even within "virtual region" that are physically separate but economically interdependent), it would make sense, while talking about "more integration" to talk also about more operational data exchanges, to allow a continuous revision of potential issues.

Not just as an ex-post element, but also as an ongoing concern that could help influence policy.

Each Member State has its own national statistics bureau, its own industrialists' association, and obviously there are already exchanges and harmonization efforts, e.g. Eurostat is a source of cross-EU stastical information.

But considering the quantity of data collected on a daily basis, we need something more dynamic and supporting decision-making than looking at last years' data.

Probably France, Italy, Germany, with their bilateral expanded and structural cooperation (up to exchanging potentially bureaucrats as well as attendance by one country's ministers to the Council of Ministers of the other country) could try some experiments in structural integration or, at least, data exchanges (to "buffer" differences in e.g. taxation approaches) that could "translate" information from one country perspective to another, enabling embedding information in decision making that could influence (or help to reduce) both the "butterfly effect" and "social resonance".

But, overall, if the aim is to "converge" on those priorities shown e.g. by the European Commission prioritization of SDGs, as well as by the initiatives on green and digital transition and RePowerEU, then probably those France-Italy-Germany tests could be a kind of "limited social experiment" before extending with others.

As, in the end, if Rotterdam dealt in 2018 with 441 million tonnes vs. Antwerp's 212 and Hamburg's 118 (see this page from Eurostat):

then it is not really the country size that matters, but the shared network of connections.

Production without logistics cannot exist, and probably the European Union too needs to move from the logistics of physical objects to the logistics of data.

Which, of course, will require a different legal framework and a faster, pro-active decision-making approach, one that would probably require a different level of trust between companies and States, to enable a continuous data flow that could influence both industrial policy and adjusting the tax and incentives system to real needs, not just to quixotic clauses hidden in hundred of pages.

And, of course, this would probably make an industrial policy and its ancillary, resulting implementations more similar to a smart contract than a traditional law.

About the latter concept: keep a look on the section organizational support, already shared a month ago an example, and will share more material in the future.

But this will be for the forthcoming book.

Have a nice week (as this article is published on the night between Sunday and Monday)

_

_