Viewed 8253 times | words: 9851

Published on 2023-12-28 22:00:00 | words: 9851

As I wrote toward the end of the previous article (Legislative reforms and direct democracy in a data-centric society: lessons from business and politics in Italy), this is actually the third one within a "shadow" series.

So, while the first article focused on the audiences, and the second on the policy side blending business and politics (actually, viceversa), this third, as announced in the latter, is focused on business.

Anyway, my concept of "business" within a data-centric society is probably somewhat different from what you would expect.

I will use as framework of reference a 2021 article that was a "digest" and contained pointers to other articles, Going smart: intermezzo on the future of compliance and regulation

As that one was somewhat long (slightly less than 10,000 words), will quote specifically few sections- but you are obviously welcome to read it before reading this article.

The key concept is that pervasiness of data, data producers, data consumers, and their mutual interactions increasingly both aware (choosing to interact) and transparent (you exist hence interact) are altering the boundaries of relationships and roles between State, society, companies, and individuals.

And this should command also a redesign of the concept and praxis of compliance, as whenever I see a new law or regulation, it always sounds a lot as if it were something from another century, not the XXI century- and often not even the XX century.

There are many areas worth discussing, and if and when will have time, will probably publish another book.

Anyway, for now, I just focus on an example that might resonate with many, and actually could inspire somebody to shift along the previously discussed lifecycle from idea to concept to project.

Hence, this article will start with a digression about Italy, and then move on across concepts:

_ Italy, the land of rights externalization

_ the case of non-profit investments

_ non-profit investment part A: private costs and social benefits

_ non-profit investment part B: social costs and private benefits

_ next step: integrating systemically

Italy, the land of rights externalization

The title of this section should have been "Italy, the land of spawning watchdogs and buffers".

Being part of the European Union implied importing some concepts, and gradually trying to "harmonize" with other EU Member States.

As I shared within that 2021 article (that will quote few times- I am lazy):

Multi-disciplinary committees may actually produce useful results- but only if they are guided by a purpose and include an understanding of the target audience.

A committee that is a mere blend of experts is inclined to reach a consensus that at least does not dis-satisfies everybody... on the committee itself.

If you are on the receiving end of the byproduct of such committees, and you still have "in house" experts covering each original "vertical" element, your organization has an advantage.

You and your team can play Cremlinologist, decrypt what you receive, and recognize, beyond the "blend", the contributing factors.

Something that, often, is useful while trying to implement.

Unfortunately, more often than not, the "audience" lacks the ability to discern the "vertical expertise" and "harmonization" elements, and receives something that, to be implemented, requires something that is missing- unless you just try to "adopt" without "adapting".

Net result?

Often, something designed to "make it simpler", and "harmonize behavior", that discounts or simply ignores the level of capabilities needed to "adapt" to the context, produces instead something else.

Apparently, "harmonizes behavior", but in reality generates additional overheads.

Adding more data implies selecting "which" data, from "which" sources, to "which" end.

So, again, a set of political choices.

Involving target audiences into rules definition about data-centric society developments is, again, a political choice- as it is deciding instead to simply issue "edicts".

Are we there?

I think we still need some tuning- not in regulations, but in roles.

The concept of "generating overhead" is something that shared in previous articles and books is something that actually observed since the 1980s and 1990s in Italy, e.g. first when a customer considered adding EDI (Electronic Data Interchange) with suppliers, then when some added ISO9000.

In both cases, instead of integrating the new compliance within existing activities, it all became an "add-on": do what you did before, and add the new layer.

My experience since 2012, and continuous exchanges since 2018 via PEC (registered email) with private and public entitities in Italy for myself and others?

Generated a collection of "cameos" that reminded me often of my times when I was paid to work as a management consultant on cultural/organizational change, using also my number crunching and decision support systems side.

Having an independent third-party is useful to solve the traditional "quis custodiet ipsos custodes".

Anyway, this requires at least few degrees of separation from the industry, something that could generate a different set of issues: where to find the industry knowledge needed to oversee industries that are increasingly more complex and overlapping.

At the same time, beside watchdogs, in Italy since decades was started a kind of "unbundling of the State".

In part it was due to the privatization of companies (sometimes covering more than one industry) that had a monopolistic or at least oligopolistic control on specific markets or market segments.

Within the Italian version of the "spoils system", where in government-owned companies it was routine to have political and "tribal" allegiance as part of the hiring process, this actually generated hybrid entities, neither private nor State, also if formally private.

There is a further side-effect of the previous structure of the internal market: having most industries with State-owned companies that followed the "Italian spoils system" implied that business choices, in most industries (from manufacturing to financial to utilities) were not just business choices.

There was always a political and social element.

Therefore, there was an element that had always been weak: oversight, as in a self-referential system neutral/bipartisan oversight is an oxymoron.

If you control both the controller and the controlled, and all works through mutual allegiance, the "oversight" takes on a different dimension.

Also the exercise of statutory rights follows different patterns: it is a routine that in Italy, before I first relocated abroad in the late 1990s, whenever there was an issue, I heard "who do we know there" and not "what is the procedure".

Since 2012, I saw that all the paraphernalia associated with the European Union implemented, from a single point of contact for citizens within each office (the Italian acronym, URP, stands for "Ufficio Relazioni con il Pubblico", but I will let you guess the most common jokes), to watchdogs and associated structures.

Interesting local evolution: apparently, whenever I had contacts with one, sooner or later was told to contact another watchdog.

So, whenever I had a single issue to solve, I had to contact multiple offices within the source of the issue, watchdogs, other entities involved by either the former or the latter, etc.

Yes, because, as customer/citizen, apparently in Italy is considered the new normal to have to deal with all the externalizations that each public or private entity decided to implement.

Sometimes I had to complain that it was somewhat quixotic to assume that a customer had to know the internal structure not just of the supplier, but also the supply chain, to get an answer (actually- to patch together an answer).

From a business perspective, if I had proposed similar "processes" to my customers whenever asked to improve their own processes or the integration of their consulting suppliers within their own activities, I would have been probably sent packing on the spot.

As the idea, generally, was to become more "lean", streamline, accelerate, not sending around on a fool's errand.

Each SNAFU (Situation Normal, All Fouled Up, a WWII acronym that I used in Italy since 2012 more often that I would like to), it becomes Kafkaesque and you start having to bounce around.

Even funnier when you write to an office, another office within the same organization from another town contacts you, and then tells you that they cannot see the details of what you are talking about because they have been delegated on the issue, but cannot access what is accessible to the originators.

I could call this Italian attitude to customer service, State and private, "sandbagging extreme".

Obviously, there is a further element, that will discuss in another section, while talking about implementing compliance.

All this implies that, in order to exercise your own rights, often you have to:

_ know what actually the party you are dealing with is supposed to know

_ provide repeatedly the same information

_ in some cases, ask for information that then you provide back to those that send it to you

_ avoid using call centers and the like, as you have no control on what they report of what you say

_ know that answers are given on what is reported, not to what you said (or even what you wrote).

Even funnier when some companies in Italy years ago tried to automate their call centers using AI, and you ended up being able to get answers only for what they had considered.

Luckily, at least with the few I checked, more recently added the obvious fall-back: talk to a human operator.

Yes, the side-effect is that, more often than I ever did in UK, France, Switzerland, Germany (to name foreign countries where, as either resident or for business had to deal with bureaucracies), "laissez-faire" turns into "laissez tomber" (i.e. from "self regulation" to "never mind").

Not really what you would expect from a data-centric society resulting from digital transformation, where the idea is to have a level of transparency and information continuity that makes society potentially more, not less, inclusive, allowing access to many.

At least, the potential positive side-effects were what e.g. was discussed in a workshop on "e-participation" that I attended in Brussels over a decade ago (you can read the proceedings from RAND here), whose final report had the optimistic title "Towards a Digital Europe, Serving Its Citizens - The EUReGOV Synthesis Report", discussing also Pan-European eGovernment Services (PEGS).

From the "objectives" section of the report:

This report is the final report of the EUReGOV project on "Innovative adaptive panEuropean eGovernment services for citizens", commissioned by the Directorate-General Information Society of the European Commission. It presents a synthesis of the outputs and deliverables generated by the EUReGOV project, leading to a comprehensive study of the phenomenon of PEGS. The report will also draw on results of its "sister project" Securegov, which was primarily concerned with the eIDM and security issues involved with developing PEGS. The purpose of this report is to provide insights in:

1. what cross-border and Pan-European eGovernment services (PEGS) are

2. how PEGS evolve

3. what their impacts are on the organisation of government services and on the relations between government and citizens / businesses

4. how PEGS development, readiness and impact can be assessed and measured

5. what possible policy measures could be taken to support the effective development and roll out of PEGS.

The report intends to provide input in the ongoing development of PEGS and the followup of the eGovernment Action Plan.

Yes, there are working examples of that, despite what some non-Italians recently told me in Turin, such as my Italian tax ID that on the back contains what I was told about by representatives of a French company at another worshop in Brussels, on eHealth, i.e. accessibility across the European Union to health services.

Anyway, here I am instead referring to the Italian approach to digital transformation and its impacts: distancing, not getting closer, citizens.

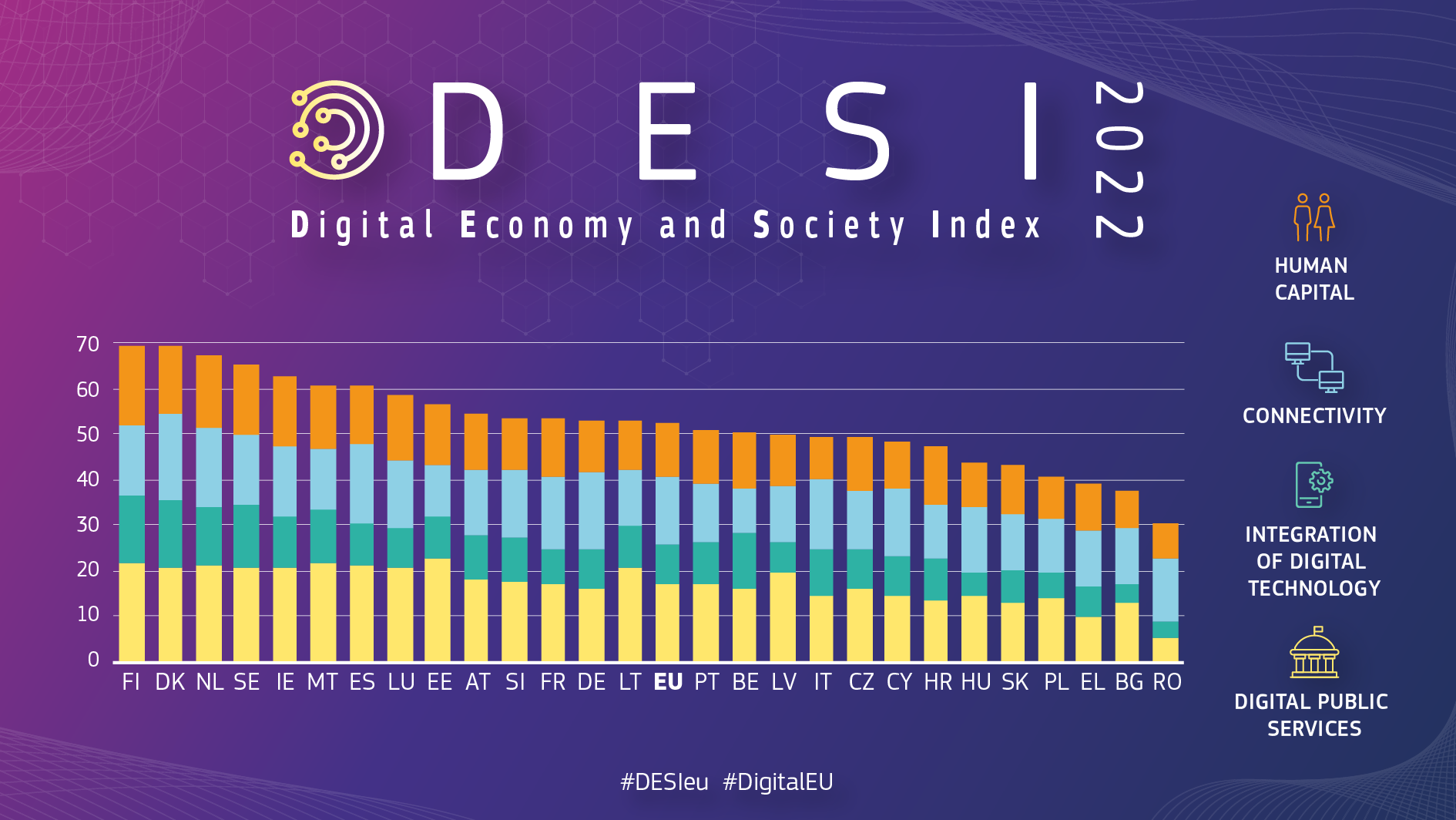

Yes, in Italy we have a digital divide issue, as shown within the Digital Economy and Society Index, where Italy improved its position a bit vs. previous years, but still is not even above the EU average:

If you look at the quote from the 2021 article that shared at the beginning of this section, you can actually see now the point from the customer/consumer/citizen perspective.

Exercising your rights should imply contacting a single point that has access to all the structured knowledge needed to provide informed responses and share such information.

If not, then all the watchdogs, URPs, etc do not replace the old consumer protection or representation entities- simply, pile up on them, and actually make them into just another cog into the bureaucratic wheel.

Why? Because your frequency of use of that information is too low to justify keeping up-to-date in a country where even watchdogs generate with gusto regulatory changes that often regulated companies simply need to be pushed to implement.

So, privatization and "leaner" approaches to bureaucracies that generated a maze of privatized, hybrid, and partially-owned private-public companies with associated watchdogs etc de facto externalized the exercise of rights.

Interesting when the approach is extended also internally within the State and local administration: a "salami slicing" approach to bureaucracy that is just the opposite of "single point of contact".

Whenever I read contracts and registration forms that supposedly deliver "transparency" on conditions, also when you have the choice to sign or not, I wonder how many can understand them.

Also, I still see often issues about implementing the GDPR on online services, from pre-filled forms, to optional choices pre-selected (you can read some material that I published about GDPR since 2018, including a mini-book).

Just this morning, in order to keep using an Italian e-banking app in Italy, I was asked to sign on three boxes before I could proceed.

Pity that one included a service authorization that I do not want and do not need, and another one was a marketing option.

None were pre-selected, but could not proceed unless selected all the three of them.

Interestingly, after selecting all three, and at last being able to click on that one, and finally having the proceed button enabled...

... got again an authorization box asking only what I had tried to select before, and asking again to authorize to proceed.

Then, of course, that e-banking app shows nowhere the authorizations that you added, or where you can remove them.

Personally, I am currently in a "limbo" for various bureaucratic SNAFUs, direct and for others, and I am curious to see if I will have eventually to decide...

... how many more volumes should add to the one that published in late 2020 (you can see a list with most of my published mini-books on change since 2012 here): three further years with bureaucracies in Italy were full of surprises.

Jokes aside, I stand by what I wrote in 2021: whenever generating rules, including supposedly to augment rights, either you make them both understandable and accessible to the intended audience, or add as a layer of compliance (i.e. for penalties for non-compliance) for those who actually are tasked to ensure the exercise of those rights, and therefore must retain the "know-how" needed to that end.

Meanwhile, I would suggest a couple of books that I am reading now in parallel, "The Roman Nobility" and Mumford's "The Story of Utopias"- both books that referenced before (as it is a re-reading).

Why? The first one is about social structure and representation across time, the second one is about the layering and structure of the concept of State.

The case of non-profit investments

To do a matrioska quote (a quote within a quote), from that 2021 article:

I think that reality will become a data-centric society using what we are assembling now.

Initially, it will be a non-hierarchical aggregation of "ecosystems", all sharing elements of "shared socio-economic-technological infrastructure" (henceforth "shared SETI"), and adding on top of them whatever their own "ecosystem bubble" needs to deliver the value added critical to attract and retain (or develop) membership to the ecosystem.

As you can see I omitted in that "shared SETI" the "political" part.

Such an omission wasn't by chance: in my view, a view that I shared often in the past, in the XXI century (and beyond) both individual citizens and any organization (including non-profit and state) will have a continuous political role through countless interactions.

So, while there will be a "professional" element to politics (as in any other occupation, there is a series of "rituals" in anything going past the most elementary level of complexity), there will be a "citizenship" part- both individual and corporate citizenship. .

The idea is that, in a society where any party is producing and consuming information, and influencing directly and indirectly how other parties behave, each and every component has a "political" role.

I shared in past articles published online since 2008 commentary about the concept of "swarming": and this is exactly what a data-centric society can enable also at the level of each individual.

About this concept, to quote another RAND report, have a look here, a 2005 report whose title is "Swarming and the Future of Warfare".

In Italy often we still are too focused on "vertical" social structures, not just because they are traditional- but also because apparently make easier what our "tribal" social structures require- control.

A "swarm" structure that self-adapts to needs is obviously something that we are used to.

While since the early XXI century in Italy discussions about what should be considered "common good" have been wide-ranging, e.g. covering from ethics to utilities, the framework of reference is still "vertical", i.e. considering really a static, not a dynamic concept of "common good".

Moreover: a static concept that derives (as you can guess) from mutual reassurances between different "tribes", not something designed for the future.

Before shifting to a different definition (and process) of convergence toward a "common good", would like to discuss a structural element.

In Italy, since the 1990s, whenever we talk about "non-profit" we think about banking foundations, basically an element within that "privatization" mix that Italy experienced in the 1990s.

Anyway, as I shared in previous articles, this actually generated yet another layer of parallel sources of policy.

Meaning: ignoring other potential sources, towns that used to be the HQ of a bank that "spawned" a banking foundation found themselves with a potential source of funding for social and local projects, as those new entities had a mandate which included to "invest" in their own territory.

You can read an outline (in Italian) of the history of banking foundations and links to associated rules and regulations here (the Italian Camera dei Deputati website).

With a catch: incumbent authorities directly and indirectly gradually saw an expanding and significant role within the foundations:

Una profonda riforma delle fondazioni bancarie è stata recata con la legge finanziaria 2002 (articolo 11 della legge 28 dicembre 2001, n. 448)

In particolare:

a) sono stati estesi gli ambiti d'intervento delle fondazioni bancarie, con riferimento a settori caratterizzati da rilevante valenza sociale;

b) sono state rafforzate le previsioni in ordine alla rappresentanza degli enti territoriali nell'organo di indirizzo della fondazione: tale partecipazione doveva essere non già "adeguata e qualificata", come originariamente previsto dal decreto legislativo n. 153 del 1999, ma "prevalente e qualificata"; sono state altresì rafforzate le disposizioni in materia di incompatibilità, nel senso di prevedere che sia i soggetti ai quali è attribuito il potere di designare i componenti dell'organo di indirizzo, sia i componenti stessi degli organi delle fondazioni non debbono essere destinatari degli interventi delle fondazioni

To summarize (if you are unwilling to deal with GoogleTranslate): local authorities shifted from having to be adequately represented to taking a lead.

With a side-effect: as banking foundations are considered "private" entities, this de facto gave elected officers a say into policies adopted by banking foundations through those appointed, with effects potentially beyond the term they were elected for.

Yes, another of those "hybrids" I wrote about, that we in Italy are so fond of.

In Italy, notably since the privatization wave of the 1990s, routinely "beached politicians" used to land a board seat or even managerial roles into one of the countless national or local "hybrid" (not just banking- also manufacturing, utilities, etc).

Due to various reasons, including history of the first half of the XX century, the presence of the State as a shareholder in Italy was wider than you would expect from a market economy.

Also if frankly some of the past privatizations could be at best defined as "quixotic", e.g. look at what still now is going on with the former flag carrier Alitalia and steel production company Ilva, that had become State-owner in the 1930s.

Some of my older readers remember a book about the privatization of USSR, "The Sale of the Century", and discussions about other privatizations that transferred around the world assets for a fraction of the book price.

Italy has a distinctive additional element: in many cases, even after privatization, or to allow the privatization to go forward, the State provided funding- as recently as a couple of years ago (while for some funding is being discussed now).

Therefore, political action as exercised practically by choices (investment, operational, even billing) of "hybrids" are yet another way of doing politics.

Or: deciding what is the "common good"- and without necessarily involving the voters, or giving them a chance to vote you out of office.

Meaning: we can have current politicians deciding how to use or dispose of assets that were generated by past operational activities and investments funded by taxpayers, and in this way also shape the future of those assets and the value that they can generate- without necessarily being still in office.

It is a matter of choices.

I am of the unusual inclination (unusual at least in Italy) that you are elected, have one or more terms, and the boundaries of your action are defined by your elective office- and those that are appointed by politicians, in my view, should leave when the politicians that appointed them leave office.

And, as I wrote in the previous article, I think that this should apply also to redistribution of powers if the proposed reforms to the Italian Constitution go ahead (hopefully along with what would make those reforms structurally sustainable).

So, again, what is "common good"?

As you would expect from what I wrote within this section- something that is not static, and that is defined by shared consensus by all the parties involved and potentially affected.

And what I state "parties", I am not referring just to political parties- but to all those involved or affected.

Also if the European Union Next Generation EU was converted within the National Recovery and Resilience Plans (including the Italian PNRR) way too often into mainly "recovery and sustain the existing while shifting the cost to the future", whatever approach is adopted to define and continuously adopt a concept of "common good" should consider also those who are not yet voters and, probably, not even yet born.

In many cases, the discussions I heard in Italy about "common good" and non-profit (e.g. including cooperatives operating within culture) sounded a bit like that 2007 funny movie that in the past quoted once in a while "Hot Fuzz", where a cop from London is over-performing and therefore affecting the bonus of his colleagues, and therefore is shifted to a small village.

Let's say the "common good" that they meant was a "static" version.

Adopting a new model implies enabling interaction, and considering also the potential benefits, not just consolidating the existing status.

Italy, as many other Western countries, is still too individualist, assuming that all the universe has to be aligned to your own individual priorities- whatever they are.

As I wrote in previous articles in this series, it might be money, power, fame, even entering into history books: but the tell-tale sign is when decisions that are derived from personal experience are repackaged as of universal interests without even bothering to build a rationale justifying that leap of faith.

It is actually really common in Italy, a country obsessed with "leadership" and associated megalomaniac tendencies.

See Il paese dei leader / The leaders' country takes a page from Vichy, that posted online in 2019, and was read by slightly less than 7,000 readers, or the shorter (but in Italian) Il paese dei leader, read by over 14,000.

In my case, the interest was putting my views on the map with an audience that never saw me working- a tough call with a CV all across the map as my own, built on "word-of-mouth" for few decades (i.e. anything but "linear", for an external observer, unless you have an interpretation key).

When I started publishing, many asked me about my "monetization"- and many were surprised when I replied that that was not my main aim.

In 2003-2005 my publication activities were represented by a quartely e-zine on change (see here, converted in 2013 into a book), in preparation of my return to Italy.

I actually invested in a direct marketing project (described elsewhere) to get an audience that could be interested in reusing concepts, and therefore generating a shared discussion ground.

When in 2005 decided that I would halt my planned return to Italy (which originally had also included merging my UK Ltd into an Italian company), it took three years to "phase-out" everything in Europe, to prepare to settle in Brussels.

Hence, my approach was to keep my skills alive by starting in 2008 to publish online under my own name (my first social media publication activities in 2007 were out of a curious episode- a dinner based only on cakes that I wanted to document), also to get used to publish for an unknown audience.

Actually, since the 1990s, and informally even before, I had only prepared reports, studies, position papers, etc for customers and partners.

In my case, I aimed for impact: which, unless you are already a known entity, requires accepting as I did with cultural and organizational change since 1990, but also with decision support systems since the late 1980s, applying a lesson learned in my early 1980s activities on political advocacy for European integration.

You need to prioritize.

What is your priority- that should be the first question.

My priority since 2008 was twofold: keep skills alive, and shift from working through word-of-mouth, to becoming a viable candidate for missions provided by those that I had not worked with before, and did not know anybody who had worked with me before.

So, I started publishing along my usual three time layers: short- (i.e. analysis and commentary on current news), medium- (i.e. a modicum of analysis and forecast on trends), and long-term (i.e. entering the realm of both projecting trends and designing business and organizational utopias).

While in Brussels, some of my older readers from late 2000s probably remember that I did experiment with an endless list of "formats": short posts, longer essays, multi-party research that was really roughly equivalent to a serialized book, etc.

It was my concept of "data-centric": you have to provide value upfront before you extract value from the feed-back, to further improve your "tuning".

As a kid, I used to say that I considered people as "radios"- I had to tune to listen and understand them, and then start communicating.

Which implies, as I did much later in politics, business, the Army, and again in business...

... listen a lot, talk a little, before, if really needed, shift to talking a lot while still "polling" feed-back to keep tuning.

Anyway, all that tuning does not imply forgetting your priorities and what you stand for.

So, my choice was "individual", but within the framework of a wider potential interest.

Why this digression? To explain how you can focus on your own priorities, but, if you integrate them within a context whose feed-back you continuously monitor, you can both "stay the course" and evolve, improve, experiment- generating value for yourself and potentially also for the whole ecosystem(s) you interact with, while extracting value from it / them.

Which is how I practice, not just define, the "common good".

Now, how does this relate to the title of this section, i.e. non-profit investments?

There are two perspective, what centuries ago generated in Italy a discussion between Guicciardini and Machiavelli about "particulare" and "universale", as remembered the late Italian President Cossiga.

Anyway, to make it clearer, I will discuss in the next two shorter sub-sections these concepts, but by discussing examples of non-profit investments starting from a longer-term perspective, i.e. systemic sustainability.

Non-profit investment part A: private costs and social benefits

If you started working in the 1980s or before, you probably remember a pre-PC, pre-Internet, pre-smartphone era.

Those were times when even having access to knowledge or expertise required some "navigation", and at least some time.

Larger companies were inclined to have in-house most of the expertise they needed, including by having long-term "consultants" who actually were almost permanently there, but "opened the door" to other knowledge networks.

A project was often something that was decided upfront, albeit I remember how already in the mid-1980s one of the first things that I was shown was a picture showing the difference between what the customer wanted, what each party involved in getting toward that end misinterpreted, and how each misinterpretation layer piled up onto he previous one.

The net result? You wanted something simple, and got what my French colleague called an "usine à gaz": a complex concoction of pipes and lines delivering the same result, but at a significant higher cost and with a continuous need to tune, fix, repair.

Move into the 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, and you see what in the 1980s was used (also by me) to keep an open dialogue with the customer (called "iterative") and tune-as-you-go-by-layering (called "incremental") had become a whole conceptual building, one of the various flavors of "agile", etc.

The think I always found funny in business consulting is how most of the innovations since the 1980s started claiming that they would streamline, make it simpler, nimbler, etc- and ended up building a whole cathedral of layers, degrees, as if they were to get through the initiation steps to select the next architect of the Temple in Jerusalem.

Why this digression about project delivery? Because any investment, including with or non-profit entities, is a project.

And any project requires, at the very least, a purpose, which then helps define the usual triad of scope, time, resources (and also helps to understand when your project is not worth continuing as is).

In Italy, for the reasons mentioned above, we had since the 1990s via banking foundations for a couple of decades a "sprinkler money approach": a bit of grants to everybody bothering to ask after filling the proper forms.

Obviously, this generated also a fair share of initiatives designed to extract grants, not to produce impact.

It is a common attitude: in mid-2000s, I remember small and medium companies, as well as potential startups asking not "we have a plan to do this and that, are there funds that could support us", but more often "which funds are available, so that we design a new initiative or startup", or even "we have this planned, how can we reposition it so that we can get funding".

No wonder than that, instead of "seeding" development, many initiatives seem to die of fade away as soon as funding ends- and how funds seem to be always scarce.

This is actually a description of Zombie businesses, something that we got used to since the COVID pandemic sudden injection of funding.

Extending banking foundations grant dispersing to cooperatives within the culture industry created yet another layer of potential moral hazard.

So, the title of this section should really be rephrased as "presenting private costs as social benefits".

In a data-centric society, the same title could instead have a positive value.

The title then would have the meaning: "assuming private costs to generate social benefits, generating mutual long-term benefits".

Which is not the concept of philantrophy, which will instead discuss in the next section.

The idea is simple: in a data-centric society, as discussed in previous sections of this article, potentially every party is both influenced and influencer.

The key element is building up trust on the exchanges.

The alternative? The cost of oversight would be excessive, as:

_ oversight requires time and expertise, i.e. resources, that are generally scarce

_ ex-post oversight fixes potentially repetitions of the past, not new/emerging patterns

_ fixing the past does not save from "adjustments" that circumvent the fix

Or: oversight is often more about "sending a message" by selecting a specific "lighthouse case" to communicate on.

Ex-post oversight is fine to seed further regulation or regulation adjustments, but probably not to pre-empt issues, and certainly not to evolve in real-time.

The "assuming private costs to generate social benefits" takes on a different dimension.

The idea is that, in order to make a data-centric enviroment, you need to have those with more structure and resources take over as an investment costs that do not generate an immediate return (i.e. are "non-profit investments"), but make the market working for all the operators.

On the macrolevel, in the past shared how a company such as Leonardo, one of the "hybrids" deriving from Italian privatizations, absorbing many Italian aerospace and defence companies, said in a conference post-COVID that they were doing such a role, to help smaller companies to be able to become a party in larger projects.

Not necessarily with themselves, but also with their foreign competitors.

The rationale? Innovation requires opening the mind, not a tunnel vision.

And many smaller Italian companies, even specialized manufacturers, have been for decades used to "tag along" with local larger suppliers.

So, helping them to be able to "project" themselves into somebody else's supply chain could help to develop new ideas, new concepts, and. eventually, new projects.

Yes, again the same "lifecycle" that discussed also in the previous article of this series, Legislative reforms and direct democracy in a data-centric society: lessons from business and politics in Italy

Companies such as Leonardo or, in the past, Bosch (that purchased an Italian company after that company, by late delivery generated a penalty from a German automaker, but was considered as having good engineering and products but management not structured enough), would need no external incentives.

Meaning: they would have their own "individual" interests as the key driver and incentive to adopt apparently "altruistic" approaches.

In their case, the innovation ability and flexibility embedded in a small company might justify taking over the costs and management structure that those companies in Italy are unable to develop.

Anyway, this requires a long-term strategic approach, something that many smaller Italian companies are unable to develop, both culturally and structurally.

If you have a limited, pre-ordered, specialty production run, as it is typical in aerospace and other industries producing "custom" products, the components might be specialized, but require e.g. manual interventions, and the volume is not enough to justify the interest of a large company.

Anyway, a smaller outfit might be able to saturate its production capacity of those components and associated tooling also with the limited production run that will eventually use them.

It is the same "making elephant dance" that I discussed in previous articles.

I know that some of my readers would think about automation etc: it might make sense in some cases, but for others the manual dexterity requires a long training period, and for the time being the human adaptability cannot be replaced.

Large companies as discussed above would have their own motivation to de facto subsidize their own suppliers' development and maintenance of organizational capabilities, e.g. to make them predictable and integrated within a "lean" supply chain that, after COVID, implies also one with a higher degree of transparency and resilience, as well as continuous communication.

As you probably already guessed, the idea is to extend this approach also to other "interactions", including "unplanned interactions".

Example: consumers/citizens interacting with their own data-centric environment in smart cities, or even using their own (or rental) vehicle with the associated large quantity of on-board data-generation and data-consumption.

If your target audience or market is consumers, frankly what I saw in Italy, and online also outside Italy, is that you can expect more of the usual "sand bagging" and ex-post watchdog interventions, which in many cases are more useful as a placebo and to justify the mere existence of watchdogs and stave-off litigation, than to really prevent or solve consumers' issues.

Living in a data-centric society requires all its components to behave as belonging to a data-centric society, and therefore the approach to regulation and law-making discussed in the previous article could evolve into an additional condition to compliance.

Instead of compliance as paper-based ex-post check (including its electronic variant), it should be embedded within operations, notably in a country such as Italy where the State has the legal means to access banking accounts and other operational information, i.e. should require integration with data sources and data exchanges.

This would require probably a long-term regulatory investment, but short-term could be implemented with existing laws and regulations (in Italy, any business has to provide plenty of data, and with e-invoicing what is missing is the "traceability" to the data that generate the invoices).

If the current e-invoicing framework were to evolve, it could allow to monitor in real-time and automatically enforce compliance, as it happens e.g. with slot machines or cash registers that are connected to networks and provide data to the State.

Shifting from invoicing to micro-instantaneous invoicing for any transaction is actually the natural, regulatory consequence of what some advocate, when they say that citizens should be able to extract value from data that they provide or transform and deliver back.

The matter is shifting from the realm of theory to that of practice.

It will take time before this latter application of "smart contracts" will be applicable, notably would require drastically redesigning the regulatory framework and integration of systems within our data-centric societies.

At the same time, it would be advisable to remove people from the loop, to avoid the typical Italian "data leak" and what already some of the current disclosure regulations could generate, i.e. releasing information affecting the competitive advantage of businesses potentially to competitors.

The latter is something that discussed in some of my previous books on the data side of change, e.g. also making data anonymous, if you cross-reference enough databases with different "views" of the same data and all nominally "anonymized", can actually disclose more than you would like.

For the time being the point would be simpler:

_ compliance should imply also adding monitored requirements to provide customers/citizens (private or corporate) with pre-emptive notification on changes within associated laws and regulations

_ such a monitoring would be part of the integration of systems, and could then be delivered to customers using the communication channels already used for billing etc

_ for instantaneous transactions, traceability should be enforced, to enable reversal if, ex-post, proved to be based on false or misleading pretense (e.g. "forgetting" to inform customers on the above).

The rationale being: it makes more sense to introduce these "update requirements" where anyway they would be needed, i.e. at the supplier level, than assuming that e.g. millions of customers have to keep up-to-date with them.

Therefore, the idea is to have a single point of cost (as part of their "cost of doing business", a.k.a. compliance), removing sand-bagging, but this way generating massive social benefits that would, in turn, be able to release more demand.

Just imagine how many hours are spent yearly for litigation and complaints, or just to stand in line or talking with service agents over the phone about bills, all interactions that could be easily avoided by integrating within compliance communication requirements.

And now, let's see the flip-side of the coin.

Non-profit investment part B: social costs and private benefits

Just a disclosure: I think that tax-deductions for philantrophy should be revised.

Reason? In modern democracies, we are supposed to vote also to decide how our contributions as taxpayers will be allocated to priorities, i.e. a political choice.

Tax-deductible philantrophy is an income-based restructuring of priorities, not really a universal right.

If I, say, I give 1mln EUR to a cause or even a non-profit initiative that is against what the majority decided to be priorities, I am de facto:

_ removing 1mln EUR from that prioritization

_ shuffling it to my own priorities

_ doing it just because I can afford the resources to "bully" my choice on other taxpayers.

Different would be if, from my disposable income, after paying taxes, I were to decide to provide 1mln EUR to a cause that I support: that would be the exercise of my political freedom to use my own money.

I know that many would disagree from the above, but, as usual, I like to talk straight, and walk my talk.

There is also the issue of what happens when, instead of just "withdrawing from the pool" for a transaction (that donation), I even set up an entity, such as a foundation, to "shield" my income so that I can redirect it to purposes that other voters and taxpayers do not like.

This would actually be a structural denial of the democratic process: generating social costs to support private benefits.

Even worse if that "shield" in reality is to support a lifestyle, e.g. creating a non-profit foundation that pays offices, staff, travel expenses- just to convert what would be business costs that are useful to enhance the image of those representing the entity into a formal non-profit, but again without being subjected to ordinary business constraints.

Decades ago, I was told of an Italian trick, to get a service contract from a customer, and then, instead of hiring staff, getting a cooperative whose employees are basically those that I would hire as employees, so that they can get only a share of the proceeds of the contract, having then a service contract with the company that organized all this.

Rationale? Paying less than the ordinary wage and associated labour costs, and, being all "shareholders" of the coop, being more "flexible" on hiring and firing.

Another side of social costs associated with private benefits is of course the continuation of "structural business reduction" grants to businesses, that not just in Italy are so popular with politicians.

Yes, COVID generated a temporary global shutdown- but under this "temporary" cap many permanent measures that instead aim to cover for the impacts of green and digital transformation, and other industry transformation.

Converting ordinary businesses that, in the past, would have shifted to another business or folded, into Zombie businesses: lingering forever, never generating anything more than survival for the owner and "gig-based" temporary staff, while never growing and never generating self-sustainable jobs that would justify those subsidies.

It is not just Italy falling into the trap of converting COVID (and now two wars) into an excuse for all the pork-barreling that you can get away with: look around you, in your own country, and look at news worldwide, and you will see many "support" plans that actually do not develop resilience, i.e. ability to withstand future shocks.

The risk is that we still will have to deliver a digital and green transformation, and prepare for systemic sustainability, but we keep procrastinating choices- and misallocating resources that would be sorely needed for all those transitions.

Next step: integrating systemically

The data-centric society concept is scary to some, an utopia to others, but, at least in OECD countries such as Italy and the EU, an everyday reality.

Many prefer to do as in Italy, cocooning behind slogans, asking for more technocracy when services fail, and then suddenly non-technocratic approaches when convenient.

I am afraid that we have to get used to blend both.

Technology, if not left in the hands of technologists, actually can, as I discussed above, help to extend our concepts of inclusiveness.

An inclusive society within a data-centric context is one where each participant is able to generate the most benefits- for the participant, but also for society at large.

Which implies also that, while in the Middle Age you did not necessarily know that a nearby village had already part of the capabilities that you needed, as instead would have been known e.g. in the centralized Roman Empire, nowadays you have no excuses.

The point is that those having those capabilities should have positive incentives to have that impact- and negative incentives not to.

It is a dynamic framework, and in the end e.g. a business, beside compliance, will have an interest, if the business sees that as a way to expand its own market or its business life.

I only partially agree with those who say that the sole corporate responsibility is to make profits.

If you make profits and kill the business environment, you are a scavenger, not a business.

In my view, a business has to think about its own future as well as its own present, implying also ensuring that there is a future- which, in turn, implies generating the potential for a future.

Is this altruism? I think that it is just self-preservation: akin to planting trees, and monitoring frequency and location of trees-cutting to allow to keep your forest-based company operating potentially forever.

If costs associated with compliance are a "cost to stay in business", you can factor those costs in while setting up the business.

Sometimes I heard small entrepreneurs in Italy complaining that with all the regulations about disposal of toxic waste, security, etc they would not be able to run their business.

I think that if your business is based on generating negative externalities whose costs others downstream will have to pick up, again you are a scavenger, not an entrepreneur.

No matter what your integrated reporting or any other fancy presentation say while you "cook the books".

In a data-centric society such as those we are currently living in and seeding for the future, having a systemic integration implies also considering impacts, at least as a self-preservation strategy, as negative externalities would eventually affect your ability to operated your own business.

Obviously, this has also impacts on individual voters: the complexity of our societies is such, that sometimes almost feels as if voting were a waste of time, e.g. because in Italy it seems as if most choices are already pre-set and anyway transcend political parties.

I do not know yet if I will vote in the forthcoming regional and European elections, but it is not because I see that as a futile exercise- it is more related to having political candidates that get through the "filter" of political parties and organizations that seem to focus on megalomaniacs who want to leave a mark, not on keeping the system going beyond their own term.

Because make no mistake: a data-centric society fully deployed is not a technocentric mechanistic "usine à gaz", it is something closer to a modern-day collaborative Leviathan as described by Hobbes than a 1984 nightmare.

So, it depends which direction you decide to move it forward or backward to, it does not have its own direction, and it does not necessarily have a manifest destiny of turning our societies into a kind of Panopticon.

Italy is still a tribal society, so tribal that years ago somebody complained that a foreign ally did not provide information about an ongoing operation against weapons smuggling, and the reply was that, whenever they provided information in Italy, they never knew who received them.

Shifting toward a data-centric society that is inclusive could actually generate in Italy more disruptions that in other societies where unfiltered access to rights is more "routine".

Integrating across society would make transparent to all where the bottlenecks are, where information is more ignored than missing, and which other cross-tribal resources could actually generate positive impacts, if only those tribal boundaries were set aside for the new "common good"- at least temporarily.

If you read almost any of my previous articles, you know that I am resolutely bipartisan and that I support adopting a more systemic approach whenever making a choice.

Meaning: yes, I am interest in choices whose positive effect I could receive, but, frankly, given the choice between a short-term option that would give me positive impacts but generate long-term negative externalities for all, and the other way around, walking the "common good" talk means accepting the latter.

Which means, data-centric reforms or not, exactly what I wrote above: if you have an issue, have the point of information and knowledge update where it can be consistently be kept aligned with reality, and then identify how to make that knowledge accessible to all those that need it, in a way that each specific audience can integrate it within its own "information lifecycle".

I know that on Facebook anybody who read few articles (or even titles of articles), or at most a single book, becomes an expert.

Frankly, I met also many experts who got their "expert badge" long ago, never bothered to follow evolutions, and still pretend to be experts- and, often, use their status as expert in A to lecture people on B C D- whatever.

In my past activities, I had to work in many industries with many experts, and actually learned to know the difference between experts, checklist-based experts, and headlines-/CliffNotes-/singlebook-based experts.

I learned from all of them, notably the boundaries of my ignorance, and keep having the latter up-to-date, whenever I am asked to do something "operational".

And whenever somebody asked me to do something that I knew nothing about, I stated the level of my knowledge and what I could contribute (my approach and experience on change and business number crunching), and absorbed whatever was needed to extend my contribution toward the agreed objective.

Proposing solutions is another area where I have to routinely check if all the information needed is available, the "known unknowns"- obviously, the risk is always the "unknown unknowns", but this is where integrating with experts helps.

Currently I am working on some data-based projects and publications, while waiting for some bureaucratic SNAFUs to be solved, before I can say "yes" to new missions (recently I had to turn down after identifying a SNAFU).

Probably eventually will have to relocate again outside Italy, as I wasted already a quarter of a century, since I first relocated abroad, to support in Italy part-time startups, companies, etc, and understand that the local rationale is a cognitive dissonance: create the issues, and then refuse to acknowledge them or cover the costs.

Therefore, for now will not release any further information under the "product ongoing" and "product available" sections of this website: those were projects that started while abroad, used also in activities, and I see no reason whatsoever to transfer for free to locals who are still focused just on their own "particulare", their own tribe- better to keep sharing online if and when feasible.

As for the new projects integrating physical and digital- for now, what I posted on YouTube a month ago is enough, and eventually will simply start "living" more of my prototypes.

Actually, follow this website, as will here and there embed some prototypes within it, as I did since the late 1990s, to see how some concepts could actually be transferred into products and services.

The other data-based projects (started in 2019, 2022, and 2023) are actually already producing some interesting information and prototypes- will share in future articles here and there some highlights, and the first one will be soon another article about a dataset that released on my Kaggle profile.

If you read up to this point, moreover if you read also the two previous articles in this "shadow series", you should understand that actually these three articles were a draft of yet another mini-book.

Worth repeating as a kind of open-ended conclusion: in Italy, we search since decades for leaders that save us from ourselves without disrupting the potential to use our traditional "relational" shortcuts.

In Italy:

_ we do not really care about rights- we care about "our" rights

_ we do not care about meritocracy, we care about our value extraction

_ we do not care about sustainability, we care about sustaining our lifestyle

_ ...

and all this with the minimal disruption and cost.

Digital and green transformation plus further European Union integration require a structural shift that we Italians preach about but are unwilling to practice, as would disrupt our "tribal perks".

The decision-making changes embedded within the NextGenerationEU and the associated Recovery and Resilience Facility, and then all that the two wars generated (e.g. RePowerEU, reshoring initiatives, etc), will have long-term impacts that still have to be "digested" in Italy more than in other EU Member States.

Personally, I hope that the next European Commission will be more an orchestra than a performance, as all these changes require orchestration, not limelight.

And I hope that, within the announced changes to the Italian Constitution, there will be a collective choice to do something more systemic, to bring the Italian Constitution into an inclusive and non-tribal non-technocratic XXI century, spawning/seeding further changes if and when needed, but within a reinforced "exoskeleton".

As, anyway, creating a more systemic integration in Italy would increase its sustainability and long-term resilience.

Something that will be sorely needed in a country whose population is expected to age, shrink, and still have to pay off faster than ever the pile of debt generated by past generations profligacy.

Including what a Minister of the current government (I never voted for him, his party, or any of the political parties within his government) just few days ago called four years of collective hallucinations (he used stronger terms), i.e. considering that temporary changes and leniency were a structural "free-for-all".

Have a nice week-end and year end!

_

_