Viewed 337 times | words: 2080

Published on 2024-08-20 17:30:00 | words: 2080

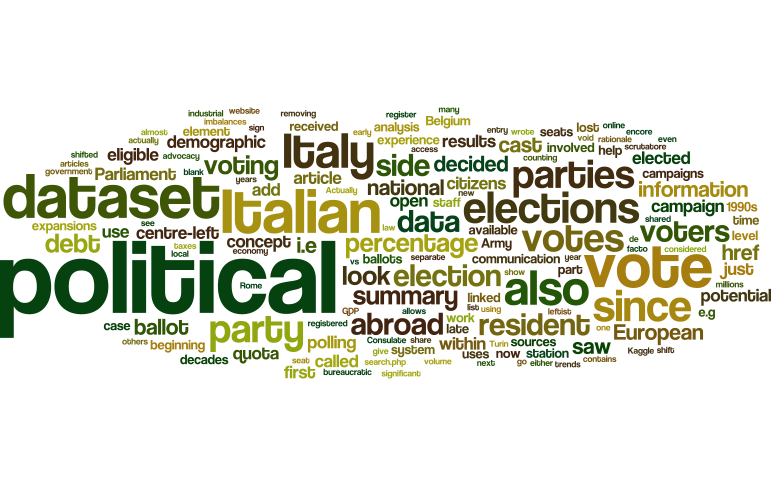

This article is to present a dataset about Italian elections since 1946, i.e. since Italy became a republic.

The dataset is a work-in-progress, and currently contains the summary data about

_ citizens eligible to vote

_ actual voters

_ blank ballots

_ void ballots

_ votes, percentage of valid ballots, seats received by the top 5 political parties.

The dataset is available here- for now, it contains the summary information about elections 1946-2022, at the national and European level.

From 1979, citizens of Member States of what is now called European Union are entitled to cast their ballot also for the European Parliament.

From 2006 Italian citizens resident abroad and registered with the Italian Consulate within the registry called AIRE can vote by mail from abroad, for a separate list of candidates who, once elected, have their seat in Rome.

This article is within the "citizen audit" section, and generally this implies that should be short and just factual.

To give a bit of backgroun on my experience with elections, campaigns, voting in Italy, I decided to add few sections:

_ background on the "bureaucratic" side of elections

_ rationale of the dataset

_ sample uses and potential expansions

Background on the "bureaucratic" side of elections

My first experience with a political campaign was as an observer as a kid in the early 1970s, in Calabria, Southern Italy (where I was with my family, moving from Turin, where we returned).

Jump forward to 1982, when I was 17 and involved in political activities with a European integration advocacy.

In 1983, at last 18, I was both involved in the above, plus decided to support the campaign of a leftist political party, to have an opposition in Parliament, as the main leftist party had been shifting for few years into a "power-sharing mode", focusing more on seats and the spoils system.

Also, as it was the first time that I had the chance to vote, decided to apply to be part of a polling station staff, "scrutatore" in Italian.

Under the Italian system, each political party had a "quota", so I was taken on board as "scrutatore" as part of the quota of the political party on whose campaign was working (my specialty: as I had seen political campaigns organization through my mother and father, to help organize mailing, but also work on events at grunt level, i.e. security, spreading leaflets and then cleaning what had been dropped by "readers" who tossed away, etc).

The agreement? I would give 50% of what I received to the party, and in exchange would receive the sandwich lunch.

Why the system had a quota for each political party? Also because, while larger and more organized political parties (incumbents) had seats and funding from prior elections to subsidize an army of volunteers to work as "rappresentanti di lista" (election watchers to verify that no funny games are done during either voting or vote counting), the quota of polling staff station informally covered the same role (also if formally were supposed to be neutral), to watch out to avoid that major political parties pushed for not counting votes for the smaller ones with interpretations of voters' intentions (e.g. it was common to have votes considered "void" if there was a minimal potential marking beside of what was marked on the party symbol, while for major parties prevailed "voters' intention").

I did an encore, but directly and not for a political party, the next time, and when was called out further, but turned down only when I when I was called up in the Army.

Then, also in the Army, due to my repeated experience, was asked to work as polling station staff in the Army internal representation elections: discovering the difference between votes in the civilian side, and votes in the military side.

Then, whenever resident abroad since the late 1990s, I registered with the local Italian Consulate, and experienced first in UK then in Belgium different ways to be an Italian voter, before starting again to vote in Italy from 2012- just in time for a couple of upheavals (2012 and 2013 saw significant changes within the Italian political scenario- frankly, more an encore than a paradigm shift).

And, incidentally, as it was allowed in Belgium for EU citizens to register to vote in local elections, I did register and vote- my first case of electronic voting.

I could add more, but this introduction is enough of a summary.

Time to shift to the purpose of this article: describing the dataset and its potential uses and expansions.

Rationale of the dataset

Italy is a country where, for various reasons, until 1994 more than 85% of those eligible to vote decided to cast their ballot, after a peak of over 93% between the late 1950s and late 1960s.

Since the early 1990s, when started the so-called "Italian Second Republic", there was an increasing fragmentation of political parties and coalitions, which actually seemed almost to change name and composition at each election.

It might be a direct side-effect, but from 85% in 1994 in 2022 we shifted to barely below 64%.

And those eligible to vote from abroad? We shifted from 39% in 2006, to 26% in 2022- not really a sign of approval of the new right-to-vote.

Maybe in the latter case also because, as I saw when I was resident in Belgium and received the ballot, voters have contacts with their representatives only at election times- then, not even communication is provided, until the next call to cast a ballot.

Personally, as I wrote also in 2009 when created a website to share the political platform of all the political parties, to "level the communication gap", I saw how really once elected get lost in Rome, almost never to heard of about.

Incidentally: since the beginning, as anyway there is a separate list, I considered that those elected by voters abroad (i.e. paying taxes where they are resident) should not be voting for what applies only to Italians resident in Italy- from taxes to regulations- but that is my own personal position, not what the law stipulates.

Actually, any Italian resident abroad remembers how at least one President of the Council of Ministers from the centre-left thanked the representative from the right who campaigned for decades to have Italians resident abroad cast their ballot, only to see that most of those elected were from the centre-left, and de facto in more than one vote were pivotal in supporting that centre-left government in Parliament (Italian political parties are quite fond of the "confidence vote" in Parliament, a kind of blank check to those presenting a Government decree to be converted into law, or legislative initiative sponsored by the governing coalition).

The interesting element is that since the 1990s political parties in Italy do with election results the same that they do with the national stockpile of debt: look at the percentage, not at the volume.

Or: consider a success getting a percentage equal to that obtained by their predecessors, also if few millions votes are lost.

On the national debt side, this attitude contributed to make acceptable to double the debt in few decades, by obsessing on the percentage vs. the GDP, instead of the volume.

If your economy loses the ability to compete e.g. by having an obsolete infrastructure and industrial machinery, and under-investment in continuous improvement of your "human capital", you suddenly wake up at a tipping point when you cannot anymore play that percentage vs. GDP game, and have to worry about the dozens of billions of EUR that have to be used to pay for interest- or refinance year after year: a de facto rescheduling.

Look at the dataset, and you will see how many millions of votes were lost, all the while fragmenting political parties, despite the growth of those eligible to vote.

Anyway, demographic trends in Italy will add few more issues both on the debt and voting side- just look at the numbers (if you are curious, look at the 24 articles so far on the "demographic" concept, and the 61 on the "debt" concept).

The rationale of this dataset is to help look at trends, and also, for those involved, potentially consider how to focus interventions to bring back voters to the polling stations.

I shared a dozen years ago my only book in Italian, on political advocacy integrating also online media with "traditional" approaches.

It would require some update, but if was focused on concept and communication, not on tools- hence, most of it probably still could be relevant, from the despicable continuous campaigns I saw since 2012, and the results that produced.

The dataset is just a summary, but allows to carry out some preliminary analysis- and can guide into looking for more detailed information that is publicly available.

Sample uses and potential expansions

There is an element of Italian politics that always disliked, notably since 1983, when I saw that those that I helped to elect did the typical middle-class Turin choice: use the political campaign reimbursements and funding post-election to turn an election into a tenure track, i.e. becoming "rentiers" by using those funds to buy apartments that would produce a revenue stream- an old political trick on my political side (centre-left) in Italy.

Nowadays, technology allows to have access to information and resources that in the past would have requires a significant amount of resources, i.e. potentially removing a barrier to entry for newcomers.

The summary dataset in my case will be used for commentary and some analysis, linked with other dataset (both those that I shared online on Kaggle, and others available from international and national sources as "open data".

Actually, if you go around this website, you will find since 2018 plenty of articles that reuse or integrate data from open sources: the concept is either using what others can use, or "curate" new datasets based on open data and analysis, to share something that anybody can use.

Being bipartisan, I vote who I decided to vote, but believe in removing barriers to entry that help only the incumbents.

Within the Kaggle dataset that linked at beginning of this article, listed also the sources of the data: if you prefer to go deeper, you can access open data that goes down up to show in each single town or village in Italy how the results were in each election.

Just focusing on my summary dataset, you could e.g. look at how many votes were needed in each election for each political party to obtain a seat- a sign of the imbalances that our Italian obsession since few decades for revisions of the electoral laws is actually creating.

That those imbalances results in those who did not won the elections routinely being part or even leading a government, is a quixotic element that I think has no small contribution to the reduction in the number of votes cast.

What is the point voting for A as an alternative to B, if then B allies with A as junior partner?

An obvious use is to look at the percentage of voters- but, if linked with demographic and urbanization data, could show also how Italy evolved since 1946.

As I wrote at the beginning, this dataset is a work-in-progress: for now limited to national and European elections, but eventually will add other information, as my publishing needs will dictate, and will link to other information related to the economy or evolutions in society and within the industrial base.

Stay tuned!

_

_